by Gail Obenreder | February 12, 2019

Joan of Arc is the stuff of both legend and history, and she’s here now in Delaware Theatre Company’s world premiere of Chelsea Marcantel’s adaptation of Saint Joan.

George Bernard Shaw’s drama opens in 1429 (during the Hundred Years’ War), when village girl Joan of Arc (Clare O’Malley) appears at the castle of Robert de Baudricourt (Charlie Delmarcelle). He’s stunned to hear her say that “God says to give me a horse and armor and some soldiers and send me to the Dauphin.” He calls for his retainer De Poulengey, also known as Polly (Sean Michael Bradley), whom Joan has convinced to outfit her, and reluctantly gives his permission.

Joan and Polly set off for the court of the ineffectual Dauphin Charles (Michael Doherty), whose coronation as king of France has been stymied by the English occupation. After close examination by the Archbishop (Dan Kern), against all odds, Joan becomes the French commander. Within two years she has led the army to victory and crowned Charles king.

Embodied voices

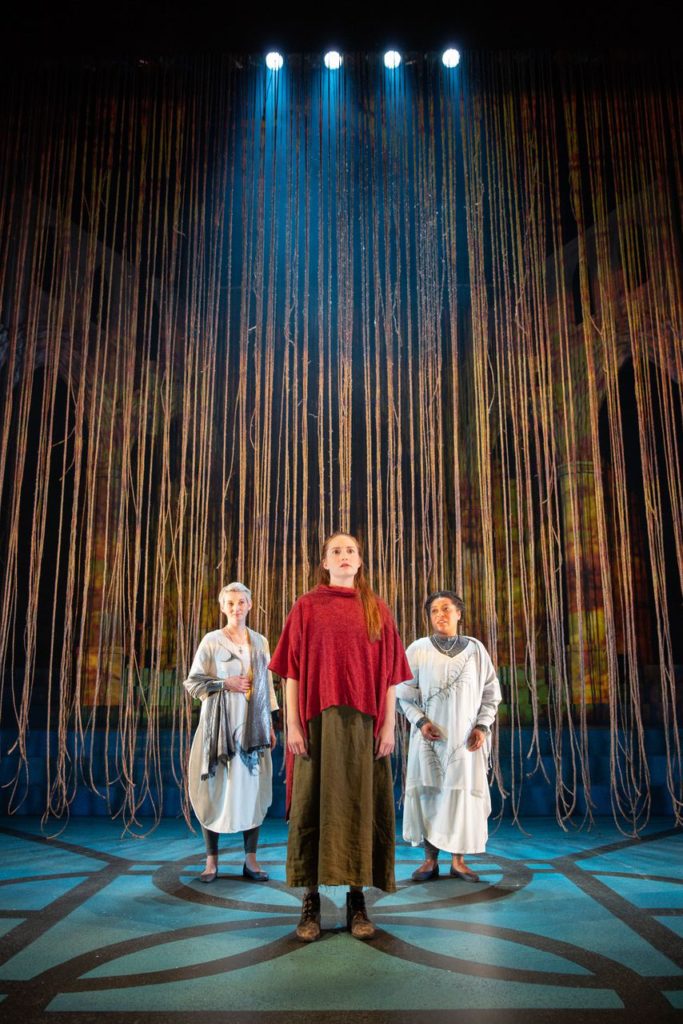

Throughout, Joan is guided by her “voices” — Saint Margaret (Mary Tuomanen) and Saint Catherine (Tai Verley), whom Marcantel has embodied. Told they are in her imagination, Joan replies, “Of course, that is how God talks to us.” And thus her fate is sealed.

She acquires powerful enemies, including the English Lady Warwick (Mary Martello) and church leaders (the company in doubled roles), who declare her a heretic and burn her at the stake. Of course, ultimately Joan is declared a saint. But as Shaw states in his preface, “There are no villains in this piece,” and its moral ambiguity is one reason the work still resonates.

Whether you’re enamored of his plays — plenty aren’t — Shaw was a literary giant, fearsome critic, and great writer. Like those of Shakespeare (to whom he compared himself), his constructions are intricately built and filled with unforgettable characters spouting his often conflicting opinions. He was fiendishly difficult and unpredictable, and his plays mirror the man. He might overthink, overwrite, and overbear, but GBS was a consummate craftsman — and tampering can be perilous.

Worthy of Shaw

But Marcantel seems to fear no peril. Like Joan facing those seemingly insurmountable powers, she has thrown herself quite successfully up against Shaw. Her adaptation adds exposition that clarifies what British audiences would have known — and probably still do — about 15th-century warfare and politics. While cutting an hour off the original, she retains much of its effective dramaturgy, including the opening “there are no eggs” scene that humanizes the long-ago characters. And she deftly inserts new (contemporary) dialogue into Shaw’s classical prose. These passages are identifiable and generally well crafted, but GBS still has the best lines and the laughs.

Marcantel follows Shaw’s own license to double: He “lumped” historical characters, “saving the theatre manager a salary and a suit of armor.” But because he constructed them to espouse and explore ideas, except for the Dauphin, they don’t have the quirks and tics that make for easy character change. It’s to the credit of the strong cast — and Martin’s crystal-clear direction — that we follow all the transitions. But role doubling doesn’t serve this particular play particularly well.

Believing Joan

Saint Joan is a prescient feminist statement: the female prophet, surrounded by men with lesser vision. So while it adds a frisson to the power structure, casting a woman — the excellent Martello — in the pivotal role of a vindictive Warwick seems arbitrary and not entirely successful.

The only single roles here are the saints and Joan herself. It’s a monumental part, and the well-cast O’Malley meets all its technical and emotional demands. Joan is both virtuous and obdurate, driven by the voices that sometimes bewilder her. O’Malley believably portrays Joan’s youth, determination, and faith, and rightly refuses to evoke pathos or ask for sympathy.

Designing the final word

Shaw “let the medieval atmosphere blow through my play,” and the designers followed. Thom Weaver’s lights throw cathedral-like shafts of stained glass or holy white light. Millie Hiibel clothes her actors in a mélange of period and contemporary wear, evoking the old while matching Marcantel’s modern arc. Music and sound by Michael Kiley imbue ancient church chants with sinister overtones. And all this takes place under Colin McIlvaine’s soaring arches, split to symbolize the brokenness of a church that condemned Joan. They carry hundreds of ropes that form an ever-changing backdrop for the remarkable videos and projections of Nicholas Hussong and Joey Moro.

The play ends with Shaw’s crafty, controversial epilogue (“I am afraid the epilogue must stand,” he said), where all the characters appear in the King’s bedchamber 25 years later to justify the playwright’s dramatic vision. Marcantel tightens this and other scenes, but luckily for us, she leaves lots of GBS to ponder, and she gives him the final word.