Click here to watch the video interview.

On Friday night, Mark and Sandra Laken will sit side by side in the front row of Everyman Theatre in the pair of seats dedicated to the memory of their late son. They will watch the opening night of a play by a writer they’ve never met about fictional characters coping with a made-up tragedy.

And they will allow a work of the imagination to help them transcend three decades of grief.

On Sept. 23, 1988, Shawn Laken was killed when his car swerved off a dark and treacherous road running through the Bard College campus in upstate New York and struck the massive trunk of a 300-year-old tree. Shawn, a 19-year-old junior at the college studying film, died instantly. His passenger and a childhood friend suffered cuts and bruises.

Thirty years ago the Lakens said they were offered the opportunity to meet the man they believe caused the crash, though at the time, police provided a different explanation for the accident. Reeling from the shock and barely able to cope with the details they already knew, the Glyndon couple declined.

Now, they’ve embarked upon a quest inspired by the plot of the Everyman Theatre production, “Everything is Wonderful.” If there is forgiveness to be offered, the Lakens are determined to forgive. If there is an act of kindness they can perform, they will perform it.

“This play could change lives,” Mark Laken said. “It’s already changed ours.”

Chelsea Marcantel’s drama is an extended meditation on the complicated nature of forgiveness.

In the show, an Amish family takes in Eric, the negligent driver who killed their two sons when his car rams into the homesteaders’ horse-drawn buggy. The crash was a result of the motorist’s negligence (Eric had been drinking and hadn’t slept for days) and atmospheric conditions (he was blinded by the setting sun).

When Sandy Laken raised her hand at a board meeting last year and volunteered to sponsor the only play in Everyman’s upcoming season that lacked financial support, neither she nor Mark knew how closely the story line mirrored the circumstances surrounding Shawn’s death.

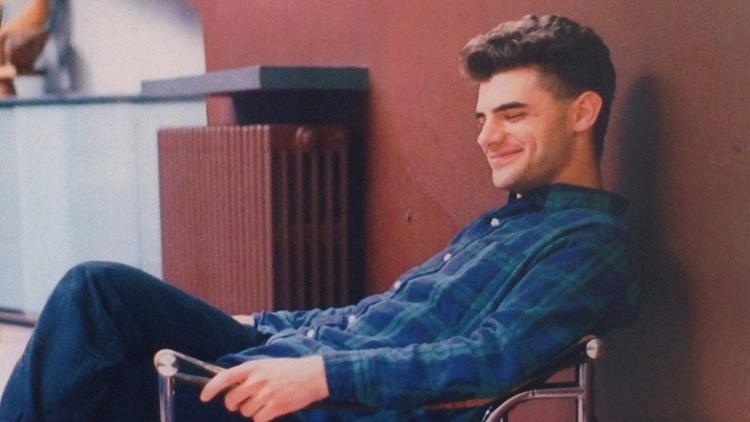

Shawn Laken was a 19-year-old film student at Bard College in upstate New York before he died in a car accident in 1988. (Courtesy of Mark and Sandra Laken / HANDOUT)

Everyman’s artistic director, Vincent Lancisi was initially pleased as he walked back to his office after that meeting — sponsorships for shows start at $10,000, though the theater declined to specify the sum for this particular production. But then Lancisi mentally flashed back to the conversation he’d had more than a year earlier when Sandy told him about the night her youngest son died.

“She burst into tears in my office,” Lancisi recalled. “She started to tremble.

“I thought, ‘Oh my God, here we are 30 years later,’ and I thought, ‘I have to call Sandy and warn her that this show might hit too close to home.’”

In “Everything is Wonderful,” Eric shows up unannounced at the farm in an awkward and culturally clumsy act of atonement. Several days after Shawn’s death, the Lakens believe, the motorist who forced their son’s 1983 Saab off the road came forward and took responsibility for the crash.

In Marcantel’s script the Amish couple refuse to prosecute Eric — just as the Lakens said they declined to press charges against the driver of the other car.

“Pressing charges wouldn’t have brought Shawn back,” said Sandy Laken, now 77. “That’s retribution, and we don’t practice retribution. It’s a waste of time and a waste of energy, and it doesn’t ever make anything better.”

Added her husband: “That’s not in our nature.”

Where the real drama and the invented one diverge is in what happened next.

In the play, the Amish family allow Eric to temporarily move in. They feed him and give him a place to sleep. Eric tackles farm chores that in the past had been performed by the dead sons.

The Lakens allowed a similar opportunity — to at least talk to the man who caused the crash — to slip away. That’s a decision they now regret.

“If we had to do it all over again, we would do things very differently,” said Mark Laken, who is 78 .

“The first question I would ask the driver now would be, ‘Tell us what happened.’ Because of lessons learned from this play, it’s easy for me now to want to forgive him and to somewhat relieve the burden he must have been carrying all these years.”

Mark Laken grew up in Forest Park and Sandy in nearby Pimlico. The two have been close friends since the 1950s, when they were in high school and went on double dates. (Each had different romantic partners.) Mark and Sandy lost touch briefly in college. But on a visit home during Sandy’s sophomore year, they ran into each other in a bowling alley and exchanged a few friendly words.

“My date said, ‘You’re going to marry that guy,’ ” recalled Sandy, who at age 77 is gregarious, a hugger and a giver of compliments.

During the next three decades, the couple raised their two boys. Andy, the elder son, was brilliant and sensitive and now lives on the West Coast. Shawn, two years younger, was “a warm fuzzy” in Mark’s words, who inherited his mother’s happy-go-lucky nature and had a zillion friends.

But Shawn also was responsible and a hard worker. Starting at age 11, Shawn held two paper routes, eventually amassing enough cash to buy a car. His parents made an additional contribution so they could purchase the sturdiest auto on the market, a late-model Saab.

“We thought it would keep him safe,” Sandy Laken said.

When Lancisi asked the Lakens if they still wanted to finance “Everything is Wonderful,” Sandy and Mark, a retired shopping mall developer, were in perfect agreement, as they usually are. They asked for a copy of the script.

“Sandy called me up a few days later and said, ‘Mark and I absolutely want to sponsor this play. Reading the script made us decide that maybe we should try to find the driver after all these years and forgive him,’” Lancisi said.

“I almost dropped the phone.”

It seems to Marcantel “a tiny bit miraculous” that something she wrote has that kind of impact.

“It’s hard to be a playwright,” she said. “We don’t get paid very much, and it’s not easy to get shows produced. Sometimes I feel as though I’m just writing into the void. This is a reminder that works of art can touch people. I can honestly say that even if ‘Everything is Wonderful’ never gets another production, it won’t matter because it has already done its work in the world.”

The Lakens realize their search to find the person who caused Shawn’s death won’t be easy. They don’t know the man’s name, and the 1988 police report of the crash originally prepared by the Dutchess County, N.Y., police department can’t be found.

Moreover, the Lakens’ understanding of how the crash occurred differs from the admittedly three-decade-old memories of the law enforcement official who responded to the call for help, and of the college president who drew on his own story of loss to console the bereft parents.

Everyone agrees that the crash occurred after a party in a dormitory. Shawn had volunteered to drive home a chum who’d had too much to drink. Another party-goer, who was following Shawn’s Saab in his own car, later told the Lakens what he remembered of the events leading up to the crash.

“Apparently the other car was coming around a very sharp bend,” Sandy Laken said.

“The weather was clear. All he remembers was seeing very bright lights, blinding lights coming directly at them. He said there would have been a head-on collision if Shawn hadn’t swerved out of the way.”

But an article about the crash published on Sept. 26, 1988, in the Poughkeepsie Journal doesn’t mention anything about an oncoming vehicle veering into Shawn’s lane.

Dutchess County Sheriff’s Department Deputy Charles Locke, the patrol officer who rushed to the accident, wishes he could clear up the discrepancy but can’t.

”It was my impression at the time that driving too fast was the cause,” he said. “But without the police report in front of me, I can’t really say.”

For his part, Bard college president Leon Botstein vividly recalls the night that Shawn died and his subsequent meetings with the Lakens. He himself had a daughter who had been killed in a 1981 car crash and he also declined to prosecute that driver, who had been speeding.

The Lakens recall that in 1988, after the other motorist came forward, it was Botstein who offered to facilitate a meeting between them and the driver. The college president has no memory of those events but defers to the couple.

“The Lakens have reason to have the sharpest recollections,” Botstein said.

“I have an autobiographical understanding of the difficulty of surviving a child’s death and I think what they’re doing, this gesture to find this man and the effort to offer forgiveness, is remarkable.

“Forgiveness is the path forward to leading a full and loving life and to finding the good you can do in the world. The gift from a death like this is the sudden recognition of what is important. You never again mistake what is essential for what is not.”

The Lakens have just begun their search for the other driver. They asked Botstein to find out what he can from the college’s end, and now they will begin the difficult process of searching for any records that might help them learn the other driver’s name. Perhaps, they think, publicity will help.

“We’re hoping that maybe an invitation will go out in the universe through this article,” Sandy Laken said, “and that the other driver will see it and contact us.”

(The Lakens can be reached by emailing press@everymantheatre.org.)

And so, on Friday night, the Lakens will take their seats in Everyman Theatre’s first row as the lights go up on scenes of an Amish countryside that’s been painted onto the wooden slats of a barn wall.

Typically, in moments of high emotion and without even looking, Sandy will reach reach for Mark’s hand. From decades of experience and thousands of repetitions, she knows exactly where she’ll find it. Mark and Sandy don’t merely clasp palms. They intertwine their fingers and hold on tight.