Sketchbook & Cut to the Quick

By Christopher Piatt

Sketchbook at Collaboraction at the Building Stage. By various authors. Dirs. various. With ensemble cast.

Cut to the Quick at the side project. By various authors. Dirs. various. With ensemble cast.

The late Sinclair Lewis memorably set his satirical novel about a journalist fighting fascism, It Can’t Happen Here, in “a town of perhaps ten thousand souls, inhabiting about twenty thousand bodies.” Were Lewis in Chicago last weekend to assess the 31 short plays that debuted at Collaboraction’s Sketchbook and the second half of the side project’s Cut to the Quick, two stunt festivals doing everything they can to stay organized and speak to their audiences, he might chalk it up as four and a half hours of fresh storefront theater played out over nine.

The events are run by polar-opposite proprietors. Collaboraction’s Anthony Moseley, the unchanging frontman for the popular tech-drenched event promoted as a rave with short plays—so, less fun than a rave—has been fending off criticism that his fest is scarcely more than a frat party with sketches since it began nine years ago. Adam Webster is the longtime gatekeeper of the side project, which recently scored with the League of Chicago Theatre’s Broadway in Chicago Emerging Theater Award (a large endorsement for an org pointedly too humble to capitalize its name). With nary a frill, Webster’s railroad-car storefront in Rogers Park almost exclusively presents unknown new plays written by, starring and performed for unknown people.

Each organization’s event could use what the other’s has. The meagerly advertised 17 playlets in Cut to the Quick would benefit from the shrewd marketing savvy behind Sketchbook’s 14 short plays; Collaboraction’s curators commissioned mouth-watering photographic portraits for each of its entries. And the juiced-up Sketchbook pieces, splayed willy-nilly on bleachers throughout the Building Stage, lack the side project’s raw intimacy and literary sobriety.

Both events offer little more than notable performance highlights, but those do give audiences a taste of what their respective theaters do best.

While most of Collaboraction’s plays this year are a wash, a small group of commissioned works devised by other fringe companies offers fun and cohesion. Andrew Hobgood and the New Colony make a bratty Sketchbook debut with “A Domestic Disturbance at Little Fat Charlie’s Seventh Birthday Party,” which uses audience volunteers to play the adult roles at a child’s party gone horribly awry. Meanwhile Mark Comiskey and the body-and-video pyrotechnics of Plasticene provide several violently different visual angles on the same mundane bowl of fruit in “The Gist.”

But two performance artists, Dean Evans and Carolyn Hoerdemann, own the evening(s). In “SpaceLab.2030,” Evans, the Neo-Futurist clown with a face like Buster Keaton eating sauerkraut, has cooked up a smashing pantomime routine of a flummoxed astronaut, synched to outstanding sound design. Wicked hippie chick Hoerdemann, in “Fix Your Teeth B*tch,” blurs music, light and (impressive) gross-out video footage of the pain she endures at the hand of her dentist. Both are grade-A dance sequences, and both briefly make contemporary theater feel, if not necessarily alive, than at least gleefully undead. (Though it’s not their fault, the slightly smug self-help theater of About Face’s LGBT Youth Program is glaringly out of place among such professionals.)

And up in Rogers Park, the plays all give you the same heady rush of vapors that Webster’s quiet, jagged ensemble pieces usually do. But their cumulative effect is numbing, and despite the steady stream of inviting new faces—the side project has always been a spigot for them—the only two that stick to the ribs trade in honest-to-God sex appeal.

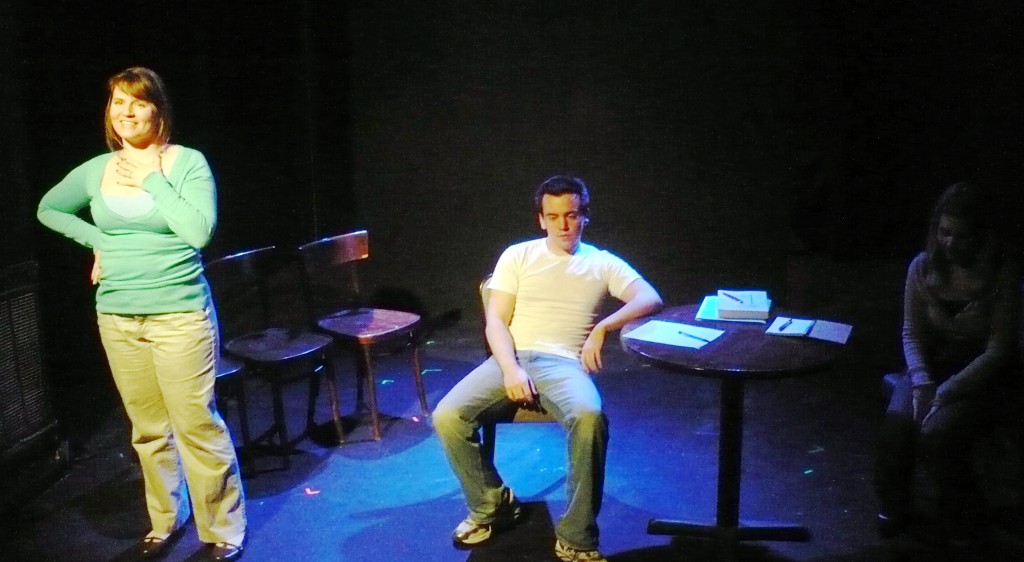

In “Ransomed Soul,” Christopher Kelly’s hypersexual dialogue may be no more memorable than his short play’s title, but he provides enough comic ping-pong for sweaty every-horndog Dan Krall and voluptuous Veronica Lake ringer Aileen May to make sizable impressions as a schmuck and his sister-in-law who can’t get each other off. And in Chelsea Marcantel’s “Stunt,” the strikingly charismatic Mike Harvey plays a high-school sophomore who breaks the heart of his lusty, lonely English teacher (Lisa Stevens), whom he remembers fondly to our discomfort.

But little else on display in these well-meaning, low-leaning festivals can offer substance to match its promotable, economical means. To wit, brevity isn’t always the soul.